Photo ©

Liz Clayton Fuller

Photo ©

Liz Clayton Fuller

Baltimore Oriole (east)

Main Focal Species

The rich, whistling song of the Baltimore Oriole, echoing from treetops near homes and parks, is a sweet herald of spring in eastern North America. Look way up to find these singers: the male’s brilliant orange plumage blazes from high branches like a torch. Nearby, you might spot the female weaving her remarkable hanging nest from slender fibers. Fond of fruit and nectar as well as insects, Baltimore Orioles are easily lured to backyard feeders.

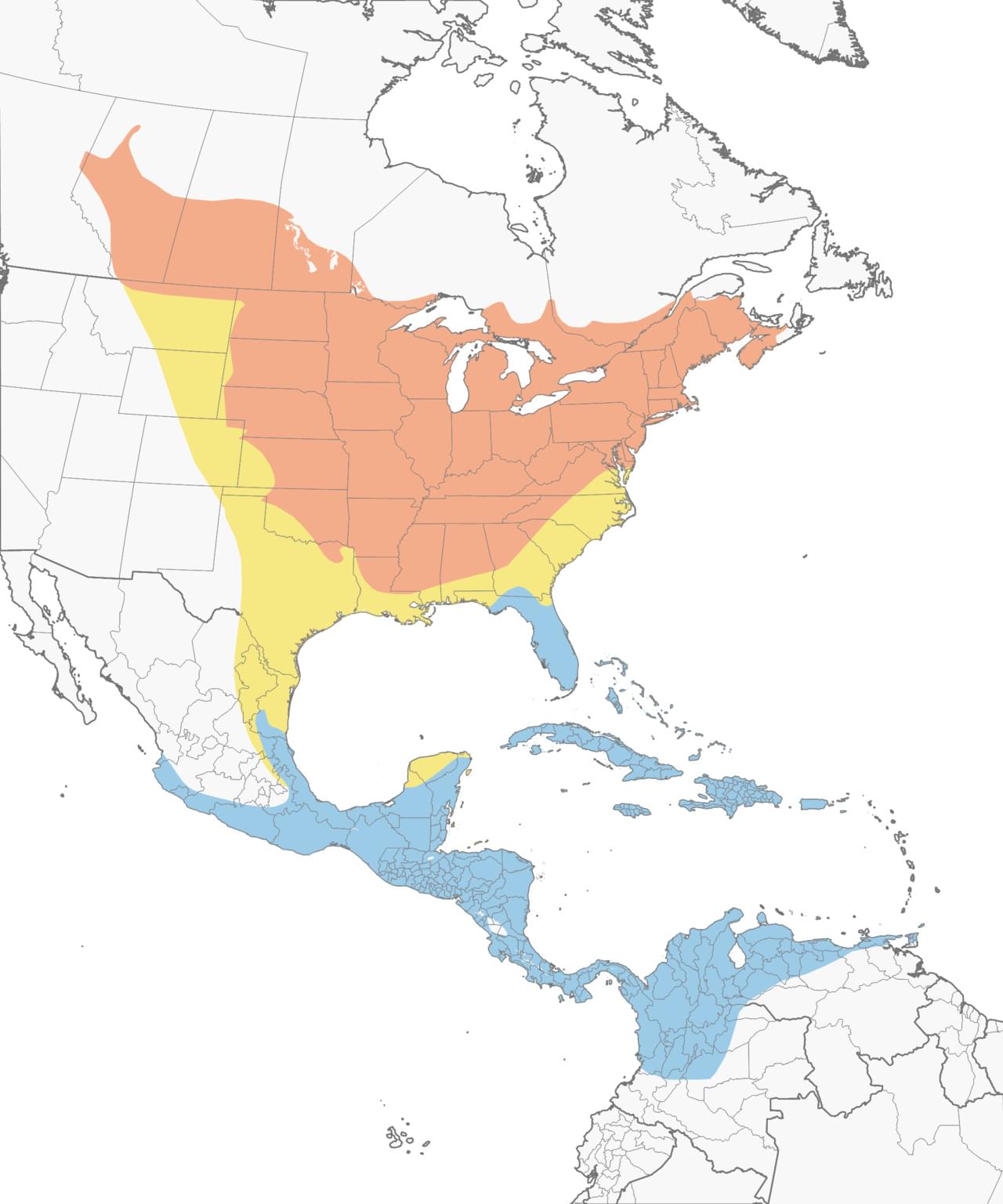

Range

Habitat

On their breeding grounds in eastern and east-central North America, you’ll most often find Baltimore Orioles high in leafy deciduous trees, but not in deep forests; they prefer open woodland, forest edge, river banks, and small groves of trees. They also forage for insects and fruits in brush and shrubbery. Baltimore Orioles have adapted well to human settlement and often feed and nest in parks, orchards, and backyards. On their winter range in Central America, Baltimore Orioles occupy open woodlands, gardens, and shade-grown coffee and cacao plantations. They frequently visit flowering trees and vines in search of fruit and nectar.

Food

Baltimore Orioles eat insects, fruit, and nectar. The proportion of each food varies by season: in summer, while breeding and feeding their young, much of the diet consists of insects, which are rich in the proteins needed for growth. In spring and fall, nectar and ripe fruits compose more of the diet; these sugary foods are readily converted into fat, which supplies energy for migration. Baltimore Orioles eat a wide variety of insects, including beetles, crickets, grasshoppers, moths, and flies, as well as spiders, snails, and other small invertebrates. They eat many pest species, including tent caterpillars, gypsy moth caterpillars, fall webworms, spiny elm caterpillars, and the larvae within plant galls. However, orioles can also damage fruit crops, including raspberries, mulberries, cherries, oranges and bananas, and some fruit growers consider these birds a pest.

Behavior

Baltimore Orioles are agile feeders that comb the high branches of trees in search of insects, flowers and fruit. They are acrobatic foragers, clambering across twigs, hanging upside down, and fluttering to extend their reach. They also fly out from perches to snatch insects out of the air. Because they forage in the treetops, they are more often seen than heard, but males often sing from conspicuous posts at the tops of trees, where their blazing orange breast attracts the eye. Both males and females may be glimpsed fluttering among the leaves, and come readily to bird feeders supplied with fruit or nectar. Many other birds defend large feeding territories, but orioles defend only the space near their nests, and so you may see several neighboring orioles feeding close to each other. When courting, the male displays by hopping around the female, bowing forward and spreading his wings to reveal his orange back. A receptive female responds by fanning her tail, lowering and fluttering her wings, and making a chattering call.

Nesting

Baltimore Orioles build remarkable, sock-like hanging nests, woven together from slender fibers. The female weaves the nest, usually 3 to 4 inches deep, with a small opening, 2 to 3 inches wide, on top and a bulging bottom chamber, 3 to 4 inches across, where her eggs will rest. She anchors her nest high in a tree, first hanging long fibers over a small branch, then poking and darting her bill in and out to tangle the hank. While no knots are deliberately tied, soon the random poking has made knots and tangles, and the female brings more fibers to extend, close, and finally line the nest. Construction materials can include grass, strips of grapevine bark, wool, and horsehair, as well as artificial fibers such as cellophane, twine, or fishing line. Females often recycle fibers from an old nest to build a new one. Males occasionally bring nesting material, but don’t help with the weaving. Building the nest takes about a week, but windy or rainy weather may push this as long as 15 days. The nest is built in three stages: first, the female weaves an outer bowl of flexible fibers to provide support. Next, springy fibers are woven into an inner bowl, which maintains the bag-like shape of the nest. Finally, she adds a soft lining of downy fibers and feathers to cushion the eggs and young.

Appearance

Typical Sound

© Matthew D. Medler | Macaulay Library

Size & Shape

Smaller and more slender than an American Robin, Baltimore Orioles are medium-sized, sturdy-bodied songbirds with thick necks and long legs. Look for their long, thick-based, pointed bills, a hallmark of the blackbird family they belong to.

Color Pattern

Adult males are flame-orange and black, with a solid-black head and one white bar on their black wings. Females and immature males are yellow-orange on the breast, grayish on the head and back, with two bold white wing bars.

Plumage Photos

Similar Species

The distinctive shape and bright colors of orioles help set them apart from most other species. Orchard Orioles are noticeably smaller than Baltimore Orioles. Male Orchard Orioles are rich chestnut, never bright orange, and female Orchard never show any orange tones. Immature male Orchard Orioles have a solid black throat (unlike the partial hood of Baltimore) and yellowish-green underparts. Bullock’s Oriole occurs mostly west of the Baltimore Oriole's range, but the two species occasionally hybridize in the Great Plains. Male Bullock’s Orioles have orange faces, a black line through the eye, and a larger white patch in the wings. Females and immature males have much grayer underparts than Baltimore Orioles. Some people occasionally mistake American Robins for Baltimore Orioles, but robins are thrushes with shorter bills, rounder heads, solid-brown backs, and a more subdued shade of orange on the breast.

Did you know?!

- With its brilliant orange and black plumage, the Baltimore Oriole's arrival is eagerly awaited by birders each spring migration. It prefers open areas with tall trees and is common in parks and suburban areas.

- Mark Catesby first named this bird the "Baltimore Bird," because black and orange were the original colors of the Baltimores, the colonial proprietors of the Maryland colony.

- Young male Baltimore Orioles don’t get their adult plumage until the fall of their second year. Instead, they look like females. Some first-year males succeed in attracting a mate and nest successfully.